Every year, the confusion over which day is Eid reminds me of that iconic scene from the film ‘Sholay’ where Gabbar Singh looks impatiently at his men and shouts in exasperation, “Holi kab hai? Kab hai Holi?” Friends seeing ‘Eid Mubarak’ messages on social media will call or text to greet me, only to find that I am still fasting and they are a day early, and I will call friends and relatives on Eid only to find that I am a day late. As the annual confusion dies down with Muslims in different places having celebrated Eid on different days as usual, and their non-Muslims friends not knowing who to wish, when and for what, a brief explanation of this phenomenon is in order.

Ramzaan (or Ramadan as it is called by some) is a month in the Islamic calendar when Muslims fast from pre-dawn to dusk. In the lunar calendar, a month begins with the sighting of the new moon, and ends with the sighting of the new moon marking the commencement of the next lunar cycle. ‘Ramzaan Mubarak’ or ‘Ramadan Kareem’ is the greeting you see trending when this holy month starts, and ‘Eid Mubarak’ is the greeting exchanged when this month ends. The first day of the lunar month of ‘Shawwal’ that follows Ramzaan is the day we know as Eid-ul-Fitr. An interesting aside is that according to traditions of the Prophet’s time (peace be upon him), any moon sighting is believed if it is reported by two Muslim witnesses in the area.

Why is the length of the lunar month unpredictable?

The lunar month is 29.5 days long, and therefore, some months of the lunar calendar are 29 days and some are 30 days long. Whether it is 29 or 30 will depend on the moon cycle. The lunar year is 354 days i.e. 11 days shorter than the solar year, and so, lunar months keep moving relative to the solar year. This is why you will find that Ramzaan falls in different seasons and overlaps with different Gregorian (English calendar) months over time. So Eid-ul-Fitr will now fall around 14th May only after 33 years, by which time, the Islamic calendar will actually have gained one full year on the Gregorian calendar. (Yes, I’m actually one year older by the Islamic calendar than I am by the Gregorian. That might explain the popularity of the Gregorian calendar.) Most Hindu calendars, by contrast, add an additional thirteenth month to the year every three years to keep the months and festivals occurring in the same seasons every year. So it’s like the Hindu calendar has a leap year every 3 years, except that this leap year has not one day but one whole month extra.

Most ancient calendars were lunar because it is based on a physically observable event i.e. moon phase. Before calendars and diaries acquired a life of their own, the date could be told simply by looking up at the night sky. If you think about it, switch off all your devices and stop your book-keeping, and you have no way of saying what day of what month it is without counting from the last date you remember. The lunar calendar, on the other hand, is nature keeping a record of time in the sky.

What decides whether the lunar month is 29 days or 30?

At any given time, the moon phase is the same all over the world, irrespective of geographical location, although the exact time of, say, 100% visibility (full moon/poornima) and 0% visibility (no moon/amavasya) varies by a few hours with longitude. For example, this month, the moon’s completely dark phase was between 11th / 12th May, with the exact moment of 0% visibility varying slightly across regions with change in longitude, e.g. 1:59 PM on 11th May in New York, USA, 00:29 AM on 12th May in New Delhi, India and 4:59 AM on 12th May in Sydney, Australia. Therefore, although theoretically, the moon was already waxing on the evening of the 11th in some parts of the world, but Eid would depend on a second factor – visibility of the moon.

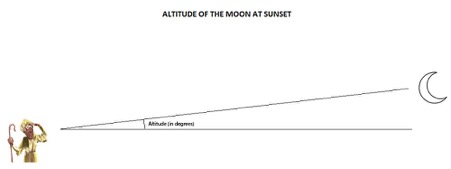

Did you know that the new moon actually rises in the morning? But the crescent moon is too slight to be visible in daylight. Although it is in the sky all day, it’s only after sunset that it becomes visible. Then, there is a small window between sunset and moonset timings when the new crescent moon is visible on the horizon just before it sets. Its visibility depends on various factors, the most important amongst which is the altitude or elevation of the moon above the horizon at sunset. The picture below illustrates what is meant by altitude or degree of elevation of the moon at sunset.

If the elevation is insufficient, the moon will not be visible as the glow of the setting sun and the atmospheric haze is maximum closest to the line of horizon. Typically, 10 degrees is the elevation above the horizon required at sunset for the moon to be visible to the naked eye, with elbow-room of another 1-2 degrees or so if the conditions are unusually clear or if viewed through a telescope or in areas of low atmospheric haze / pollution. The angle of elevation of the moon at sunset on any given day is different at different points on the globe, and the angle decreases as we travel from west to east. The following table shows the sunset time, the moonset time and the degree of elevation for some major cities by way of illustration:

| City | Sunset | Moonset | Altitude of moon at Sunset (in degrees °) | Date |

| Auckland, New Zealand | 17:24 | 17:41 | 2° | May 12th |

| 17:23 | 18:14 | 8° | May 13th | |

| Sydney, Australia | 17:04 | 17:23 | 3° | May 12th |

| 17:04 | 17:58 | 9° | May 13th | |

| Peshawar, Pakistan | 19:05 | 19:42 | 6° | May 12th |

| 19:06 | 20:39 | 16° | May 13th | |

| New Delhi, India | 19:03 | 19:37 | 6° | May 12th |

| 19:03 | 20:32 | 17° | May 13th | |

| Kochi, India | 18:38 | 19:10 | 7° | May 12th |

| 18:38 | 19:59 | 17° | May 13th | |

| Makkah, Saudi Arabia | 18:50 | 19:29 | 8° | May 12th |

| 18:51 | 20:22 | 18° | May 13th | |

| New York, USA | 20:03 | 21:05 | 10° | May 12th |

| 20:04 | 22:05 | 20° | May 13th |

(Source: https://www.timeanddate.com)

As can be seen in the table, on 12th May the elevation of the moon at sunset was 2 degrees in Auckland, New Zealand, 3 degrees in Sydney, Australia, 6 degrees in Peshawar, Pakistan, 6 degrees in New Delhi, 7 degrees in Kochi, Kerala, 8 degrees in Makkah, Saudi Arabia and 10 degrees in New York, USA. Therefore, the moon would definitely not be visible in Auckland and Sydney, was very unlikely to be seen in Peshwar and New Delhi, was quite unlikely to be seen in Kochi, may have been seen in Makkah depending on other conditions and would be fairly clearly visible in New York. Last year, some African countries such as Morocco, Somalia, Mauritania, Ethiopia, Senegal and Mali were the first to declare Eid, when the angle of elevation of the moon was simply too low for it to possibly be visible, leading to a meme and counter-meme fest on the internet and some astronomy centres seriously speculating that Africans must have mistaken Venus or Mercury for the Moon.

How it’s done

So now, with the above data, how do we decide when to celebrate? This is where differences arise. Different Muslim communities have different methods for determining their calendar that they subscribe to culturally / nationally. Now, as I said, the degree of elevation on the moon at sunset on any day of the Gregorian calendar is known in advance. You can find this data for each day of every year on the website timeanddate.com. Therefore, the Australian National Imams Council simply calculates the angle of the moon at sunset as has been done in the above table in advance and decides when the moon should become visible based on its pre-calculated elevation at sunset without bothering with factors that may actually affect visibility on that day like pollution and cloud cover. Small immigrant Muslim communities in European countries often follow the calendar in Makkah or their native country.

Meanwhile, the Dawoodi Bohra community in India follows a unique ‘Misri’ or Egyptian calendar of their own that has been fixed relative to the solar calendar. Theirs is thus a perpetual calendar with alternate months having 29 and 30 days and a leap year every four years where the last month has one extra day. Their Ramzaan and Eid dates are, therefore, known years in advance and are often different from everyone else’s. For instance, the Bohra community celebrated Eid on Wednesday, the 11th of May this year, a day before almost anyone else in the world.

In India and a number of Asian countries we subscribe to “seeing is believing” and assume that the month is 30 days unless the moon shows up and proves otherwise. Saudi Arabia, as usual, is confused and stuck in no-man’s-land, torn between Islamic traditions and all things American, with 8 months of their calendar year being fixed in advance and 4 months containing the festivals of Ramzaan, Eid-ul-Fitr and Eid-ul-Zuha (the time of the Hajj pilgrimage) being determined by moon sighting. Of course, this brings more errors into the system as the fixed months reduce the flexibility of the remaining 4 months.

In India, Kerala being by the sea on the western coast and experiencing lower pollution levels has the advantage of greater visibility over the horizon as the moon sets into the sea. The altitude of the moon is also slightly higher in the Kerala sky. Therefore, the likelihood of Kerala seeing the moon earlier than the rest of the country is typically somewhat greater and consequently Kerala is often one day ahead of most other States of India in their declaration of the start of Ramzaan as well as Eid. It may also be relevant that Kerala has much closer ties with the Arab world compared to the rest of the country. Kerala had been on a trade route with the Arab world for centuries, and this was the reason Islam came to Kerala before the rest of India. Also, practically every household in Kerala has one or more members in the ‘Gelf’ i.e. Saudi Arabia or the UAE, therefore, for this reason also, their celebrations are more likely to concur with that region. On account of a mix of these factors, Kerala typically declares moon sighting a day earlier than the rest of India. There is often another problem. For example, this year, Makkah and Kochi sighted the new moon marking the beginning of Ramzaan on the night of 12th April i.e. a day earlier than New Delhi. Since the margin of error is only one day, meaning the lunar month is either 29 or 30 days long, the latest that Eid could be in these places was 13th May, moonsighting or no moonsighting. Eid in Kerala, therefore, could not have coincided with New Delhi as that would take Ramzaan into a 31st day for them, which is not possible in the lunar calendar.

Most other Muslim communities of the sub-continent have traditionally been deeply rooted in their local traditions and celebrate their festivals based on moon sighting in their own cities, without worrying about who is doing what in which other part of the world. Therefore, since moon sighting in New Delhi and the rest of the Indian mainland happened only on the 13th evening, Eid in these parts was celebrated on 14th. While this can sometimes lead to absurd situations like cities separated by a few hundred kilometers celebrating Eid on different days, some of us have come to love this endearing suspense of chaand-raat of Ramzaan and Eid-ul-Fitr. I, for one, love the annual “Eid kab hai, kab hai Eid” moment” that is our contribution to chaos in the cosmos. I remember occasions when we have called up our relatives in other towns and cities and hit our heads against the walls to find that we are having to continue fasting stuck between cities on our east and west celebrating Eid. It is noteworthy that this only happens on Eid-ul-Fitr since Eid-ul-Zoha or Baqr-Eid falls on the 10th day of it’s calendar month (Zilhij) and so we know the date of that festival at least 10 days in advance.

Some people chaff at the difference in dates in different regions and believe that there should be a common date of Eid across the world. It is true that is does create a logistical problem, since things like bank holidays have to be fixed in advance and cannot wait till the previous night. This year, for instances, banks in India were closed for business on 13th and ended up working on the actual day of Eid in most parts of the country. But the way I look at it, this adds an element of local connect to a global religion. In a country where ‘thinking globally and acting locally’ has now come to be acknowledged as a stroke of genius, we must appreciate that here too, Islam was far ahead of its time.

(Nizam Pasha is a Delhi-based lawyer. He can be reached via Twitter @MNizamPasha.)